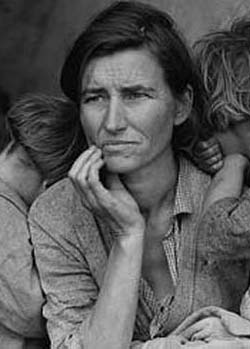

A few years ago I was asked to curate an exhibition about special collections at the Bancroft Library at the University of California in Berkeley. I chose to highlight the work of Dorothea Lange. We exhibited an enormous print of Lange’s “Migrant Mother,” the iconic image of American motherhood, anguish, and suffering during the Great Depression. “Migrant Mother” is frozen in time, nameless, with her children huddled against her, almost hidden from view. She was part Cherokee, and this adds to the sense of someone exiled in her own land. She was stopped in a migrant camp with a man she took up with after her husband died picking peaches in another camp. He was buried in a pauper’s grave. The Migrant Mother had six of her children with her in the camp, and another was on the way.

Other pictures in the roll that Lange shot that day show a fussy infant at breast (not the static, peaceful infant of a Renaissance portrait), the shabbiness of the camp at Nipomo, facial expressions in transition, decomposition. This one lasting image seems to have been carved from stone. Roy Stryker considered it the emblematic picture of all the 160,000 images he commissioned for the government’s vast documentary project.

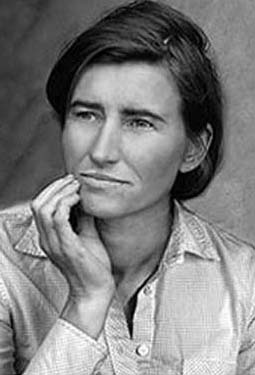

Around the time of the exhibit, the New York Times published a version of this picture in its Sunday fashion supplement. This Migrant Mother had been Photoshopped to illustrate an article about cosmetic surgery. All her wrinkles were gone, her face smoothed to generic elegance. It takes a lot to shock nowadays, but I was truly shocked by this vandalism in the name of improvement.

The other day I searched the Internet for the source of this doctored image. I was curious about any permissions that might have been granted to the artificer. But I don’t think permission was sought or required from Lange’s estate or from the Library of Congress, which holds the FSA archives. The image belongs to us.

The improved Migrant Mother was an April Fool’s hoax by the magazine Popular Photography. Many were as shocked as I was, and felt that this stunt was a trivialization of motherhood and a perversion of Dorothea Lange’s work and the history of the Great Depression.

The subject of the photo, Florence (Owens) Thompson, has spoken up in recent years, noting that she “never made a penny” from being the subject of such a famous image. She insists that Lange promised never to publish the pictures. Anonymous and everywhere available against her will, the subject of the photograph chose to put her name to her image.

When “Migrant Mother” appeared in newspapers the week it was taken, in March of 1936, it triggered an enormous response from various communities and from the government. Trucks arrived one after another with blankets, food, soap, supplies of all kinds, mechanics to help with car repairs—but Florence Owens had already moved on.

Now her grandson, Roger Sprague, the son of one of the little girls in the picture, has a web site where he sells T-shirts printed with the iconic image and the words “Migrant Mother” emblazoned in Gothic script.

What if the model for the Madonna in a Renaissance painting had a grandson who hawked copies of that painting with his autograph on each copy? Weren’t the medieval churches surrounded by vendors selling saintly relics and phony bits of the true cross to pilgrims in search of miracles? Wherever there is piety there are versions of precious originals for sale.